|

| St. Martin and Pannonia - Poster |

A historical and archaeological exhibition titled St. Martin and Pannonia opened at two venues, in Pannonhalma and Szombathely. The exhibition is the most important scholarly element of the Saint Martin Memorial Year, held in commemoration of the 1700th anniversary of the saint's birth. The exhibition focuses on five centuries in the life of Pannonia - from the time of the Roman Empire to just before the Hungarian conquest, and provides and insight into the spread of Christianity in the region.

Saint Martin was born in 316 in the Roman province of Pannonia near the city of Savaria, what is now Szombathely. The son of a wealthy military officer, he was required to join the cavalry when he turned fifteen. He became baptized in 339. His good deeds and his compassion and empathy for the poor became legendary and by popular demand he was appointed to bishop of Tours in 371. He was always regarded as one of the most important saints in Hungary, and now the anniversary of his birth provides a chance to have a look at the era when he lived, and also the centuries following the fall of the Roman Empire.

This twin exhibition of international significance gathers hundreds of objects, largely stemming from Pannonia (nowadays western Hungary), coming from a number of Hungarian and foreign collections. The exhibition opened on June 3rd, and will remain on view until September at both the Iseum Savariense Museum in Szombathely and the Museum of Pannonhalma Archabbey. At Szombathely, visitors can trace the history of Pannonia and Savaria back to the Roman roots of the time when Saint Martin lived, whereas in Pannonhalma the age of Saint Martin, the Christian monk and bishop is in focus, as well as the subsequent centuries.

|

| Fondo d'oro, 4th century (Hungarian National Museum) |

The exhibition features a number of unique objects: the earliest piece is beautifully executed bronze statue of Fortuna from the 1st century. A large blue glass vase from the 4th century represents the sophistication of Roman culture in Pannonia (pieces of the Seuso Treasure could represents this as well - but none of those were available for loan).

|

| Blue jug, glass, 4th century (Kaposvár, Rippl Rónai Museum) |

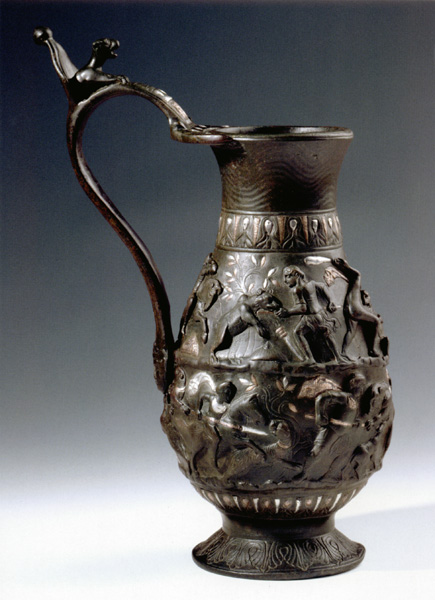

The exhibition also presents a great selection of objects from the Migration Period: finds from a hun grave of Pannonhalma from the 5th century, or a unique Early Byzantine bronze jug with hunting scenes, found in an Avar period cemetery at Budakalász (for a 3D view, click here). Objects with Christian symbols (especially the cross) are featured from several early medieval treasure finds, such as the golden Treasure of Nagyszentmiklós (Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum).

|

| Jewelry of a Germanic woman, 5th century (Hungarian National Museum) |

|

| Bronze jug with hunting scenes, c. 500 (Szentendre, Ferenczy Museum) |

|

| Dish 9 of the Nagyszentmiklós Treasure, 7th century (Wien, KHM) |

The exhibition is accompanied by a richly illustrated scholarly catalogue, and English-language edition of which is in preparation.

Further information (and advance tickets): www.szentmarton-pannonia.hu and on the website of the Via Sancti Martini European Cultural Route.

Photos via www.szentmarton-pannonia.hu.

.jpg)